Oil spill oil takes different forms. It can manifest as an iridescent sheen, a viscous stinking black layer, tarballs, an orangeish mousse.

Oil spill oil takes different forms. It can manifest as an iridescent sheen, a viscous stinking black layer, tarballs, an orangeish mousse.

Oil spill regulars can weigh the effects of different oils on smirched animals. Bunker C Crude versus diesel? Diesel is worse.

Spilled oil changes. Last week I visited the Deepwater Horizon wildlife rescue center in Fort Jackson, Louisiana (since moved to Hammond, Louisiana, to be out of the hurricane evacuation zone). Among the birds were many young birds. Not nestling babies, not reckless teenagers out on their own, more like bird children. Old enough to walk around, go down to the shores of nesting islands, play in the water, and get oiled by the sheen on that water.

Good news was that rescuers aren't seeing oil burns on these birds. Oil often contains volatile chemicals like toluene and xylene (the ones you smell when you walk past the nail salon), benzenes, sulphates, things that can burn skin, eyes, and lungs.

Jay Holcomb, the director of IBRRC (the International Bird Rescue Research Center, which along with Tri-State Bird Rescue is running four oiled-wildlife centers in the Gulf states), compared this to a previous spill in Louisiana. That also happened in nesting season. “We had 1,000 baby pelicans. Only 250 lived – they did really well. The rest died because they were sunburned from the oil,” he says. “We learned a lot about how to raise baby pelicans.”

The Deepwater Horizon oil had a long way to drift before it hit the nesting islands. Apparently a lot of volatile compounds evaporated on the way. So, no burns.

“It's a different kind of oil. It's actually easier to get off than the Cosco Busan,” an IBRRC worker tells me. (In that San Francisco Bay spill, the container ship Cosco Busan hit a pier of the Golden Gate Bridge, spilling 50-55,000 gallons of bunker fuel oil.)

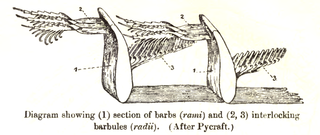

Any kind of oil that gets on birds' plumage can kill them. We used to hear that birds were kept waterproof by natural oils in their feathers, but that's not exactly right. It's the feathers themselves. Feather by feather, vane by vane, and barb by barb, plumage slides in place to make a perfectly waterproof shell over a bird's skin. Down feathers next to the skin hold warmth. Natural oils from a bird's preen gland condition the feathers. But feather structure, correctly aligned by preening, is what waterproofs an aquatic bird.

Other kinds of oil disrupt feather alignment. Feathers clump and pull away from each other. Water can get in next to the bird's skin. Birds, who run at a higher body temperature than people, get chilled fast.

A single non-waterproof spot in a bird's plumage where water leaks in will gradually soak the whole bird. One spot of oil can do this. If you have the bird in a pool, you will see it ride lower and lower as the water soaks in and makes it heavier. A wild bird may head for land when it finds itself sinking.

Bird rescue facilities like to have warm-water pools so they can test the birds' waterproofing without getting them chilled. That's one advantage to an oil spill in the South in the summer. I visited the bird rescue center in Theodore, Alabama. “The nice thing about this heat, this oppressive heat, is that the animals don't get cold,” said Californian Michelle Bellizzi. “The birds are way more used to this than I am.”

Petroleum oils aren't the only ones that can kill water birds. A few years ago there was an outbreak of desperate oiled birds stranding on the California coast. Forensic analysis of the oil was done to figure out its source. It turned out to be fish oil, dumped by some fishing boat, just as deadly to seabirds as anything pumped from under desert sands. You could kill birds with extra-virgin olive oil.

The name of a 1991 incident tells the story: the Wisconsin Fire and Butter Spill. (Hard to believe, but melted butter is not always a good thing.)

For that matter, if you don't completely rinse the detergent solution off the birds after you wash them, that disrupts their waterproofing too, and can kill them just as quickly as the oil it washed off.

But thorough washing and complete rinsing, followed by the bird's intensive preening, can do the trick.

Leave a reply to Fred Wickham Cancel reply